William Archibald Dunning recounts how President Grant refuses a third term in language so equivocal that it amounts to encouragement for his partisans. The result is a Congressional warning and the nomination of Rutherford B. Hayes.

William Archibald Dunning recounts how President Grant refuses a third term in language so equivocal that it amounts to encouragement for his partisans. The result is a Congressional warning and the nomination of Rutherford B. Hayes.Not long after Grant's second inauguration in 1873, the New York Herald, in the mere exuberance of a notorious sensationalism, broached the idea that the president was scheming to secure a third term for himself. The idea was taken up with joy by hostile journalists and politicians, and was nursed and developed into a portentous bogey duly dubbed "Caesarism." No thinking person, save Democratic politicians seeking political capital, attached any importance to the agitation, which was kept up, with obviously hard labor, throughout the elections of 1874. In the spring of 1875, however, the president played into the hand of his enemies by writing for publication a letter in which his declaration that he was not a candidate for another nomination was so carefully qualified as irresistibly to suggest that he would willingly accept it. The letter gave a new aspect to the maneuvers of the administration wing of the Republican organization. At the same time it stimulated conclusive demonstrations that the party as a whole could never be brought to acquiesce in the perpetuation of Grantism. At the opening of the session of Congress in December, 1875, a resolution passed the House, by a vote of 234 to 18, declaring that a third term would be "unwise, unpatriotic and fraught with peril to our free institutions," and the majority included two-thirds of the Republican members of the House. In such an expression of feeling there was no encouragement for those who had been watching for a chance to press Grant to the front, and the administration politicians passed definitively to the work of nominating either [Roscoe] Conkling or [Oliver] Morton.

The Republican convention met a Cincinnati, June 14, 1876. Its outcome was a radical platform and a reform nomination. With [Orville E.] Babcock, [William W.] Belknap, and the whole unsavory record of the administration fresh in their minds, the committee on resolutions could hardly frame an inspiriting appeal for support on the basis of the party's recent achievements. Hence the only clauses that embodied anything of the positive and aggressive tone familiar in platforms were those reciting the party's achievements in dealing with slavery and rebellion, and those denouncing the Democracy, and specifically the majority in the House of Representatives as supporters of treason and as foes of the nation. This species of "bloody-shirt" waving was obviously the species that Mr. [James G.] Blaine had designed, and his choice as nominee would have been the appropriate accompaniment of the platform. But though he was far in the lead of every other candidate in number of delegates, the extreme radicals and the extreme reformers alike opposed him. The result was an eventual recourse to a "dark horse" — Governor Hayes, of Ohio — whose availability was of just that nebulous type which bulks largest to a tired delegate in despair of getting the man of his deliberate choice.

Hayes was nominated on the seventh ballot, and Congressman [William A.] Wheeler, of New York, was speedily named for vice-president. Not till his letter of acceptance appeared was the precise quality of Hayes's Republicanism generally known. In that document he proclaimed with the utmost distinctness his abhorrence of the spoils system and his purpose to extirpate it, pledged himself not to accept a renomination, and announced in respect to southern affairs a desire to "wipe out forever the distinction between North and South in our common country." These sentiments left no room to doubt that the Republican nominee belonged to the reforming wing of the party.

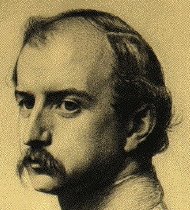

The American Nation: a History. Volume 22: Reconstruction Political and Economic 1865-1877 by William Archibald Dunning. Series Editor: Albert Bushnell Hart. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, no date. (Copyright 1933 by Edward S. Cole.) 298-301.

Also See:

- Adams's Education is Advanced by President Grant. Young Henry Adams, already an eye-witness to the Italian struggle for independence and Secretary to the United States' Ambassador to Great Britain (his father), votes for Ulysses S. Grant in the 1868 presidential election and looks on with interest to see how matters will unfold.

- Grant Tries for a Third Term (1880). Edwin Erle Sparks describes how, the 1880 Republican convention began with Ulysses S. Grant well in the lead and ended with James A. Garfield -- the darkest of dark-horses -- walking away with the nomination.

- Bartram Seeks News of the Creeks and Seminoles. About to ascend the St. John's River, in April of 1774, Wiliam Bartram seeks information about a recent incident between the local settlers and Indians.

- Audubon Observes Florida Sea-Turtles. During an 1832 trip to Florida and the Tortugas, the naturalist James Audubon had the opportunity to study the region's large Turtles...

- Be sure to check out the Browser's Guide to the Library of Babel.